Allyson Mitchell

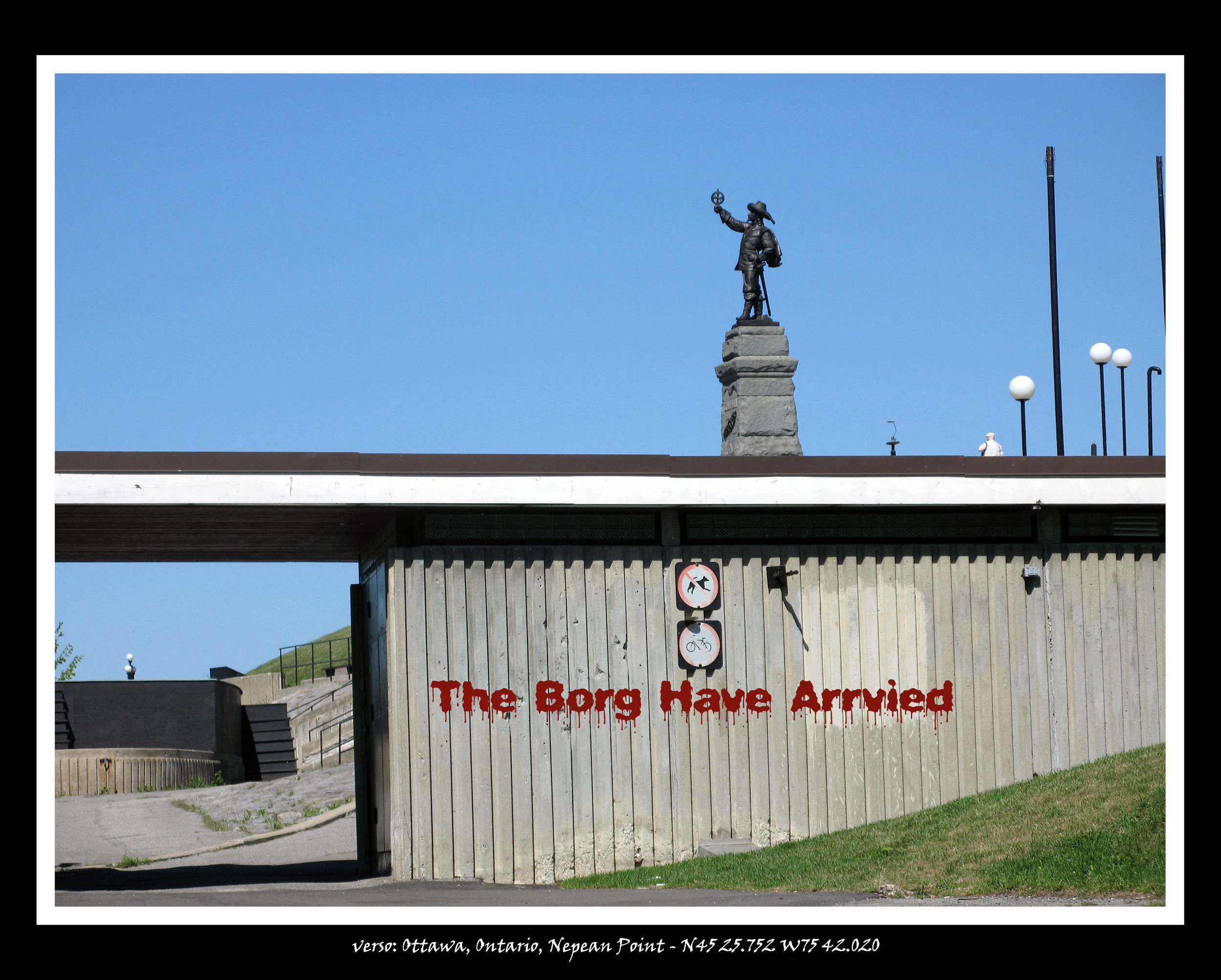

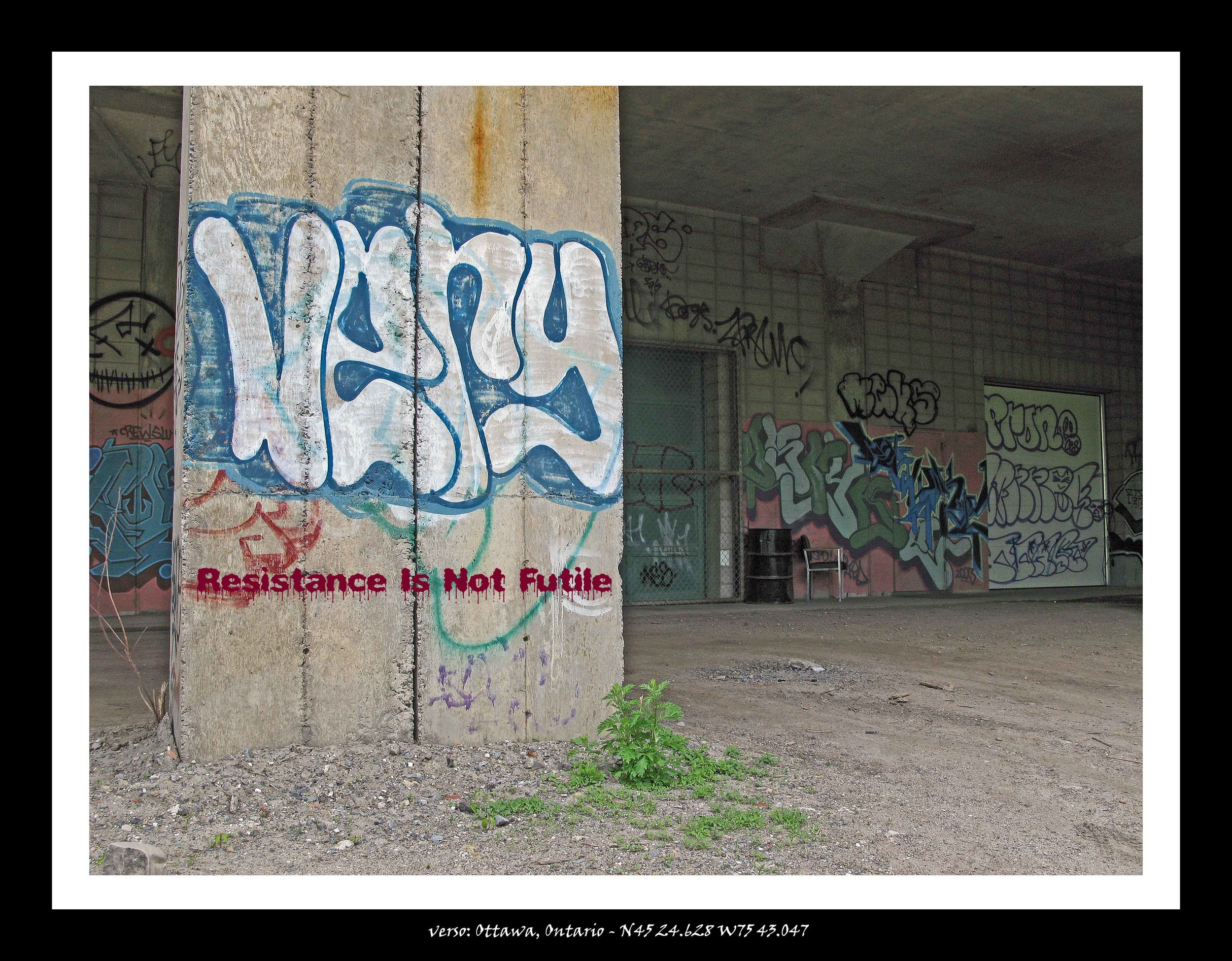

Ladies Sasquatch is a large scale installation consisting of six gigantic and 25 smaller she-beast sculptures presented on a stage/platform measuring 10 feet x 10 feet. The exhibition includes a soundscape consisting of collaged music samples and nature sound effects. The six giantess sculptures represent lesbian feminist sasquatches. The elements of the installation are constructed with appliqué borg, found textiles and taxidermy supplies and influenced by photographs found in Playboy magazines from the 1970's and by the bodies of real fat activists. Buried in the memory banks of collective popular culture is the mythical and spiritual creature called Sasquatch. Aboriginal ideas about Sasquatch (or "Wildman of the Forest" as he is called in the US and Sabe or Big Foot in Ojibwe cultural terms), have been appropriated by the white Canadian mainstream settler culture, arguably as an expression of racist fears around the "otherness" of native culture and nature in general. In traditional Western thought, the female body has been associated with nature, chaos and irrationality, and the male with order and rationality. Ladies Sasquatch is meant to work as a point of departure for thinking about decolonized, queer, politicized bodies, sexuality and communities. In an attempt to imagine different sexual currencies Ladies Sasquatch valorizes cellulite, dirty fingernails, tattoos, big butts, fangs, collectivity and collaboration. The creatures in Ladies Sasquatch marry popular culture, native iconography and radical dyke culture to create a kind of queer utopian dream world.

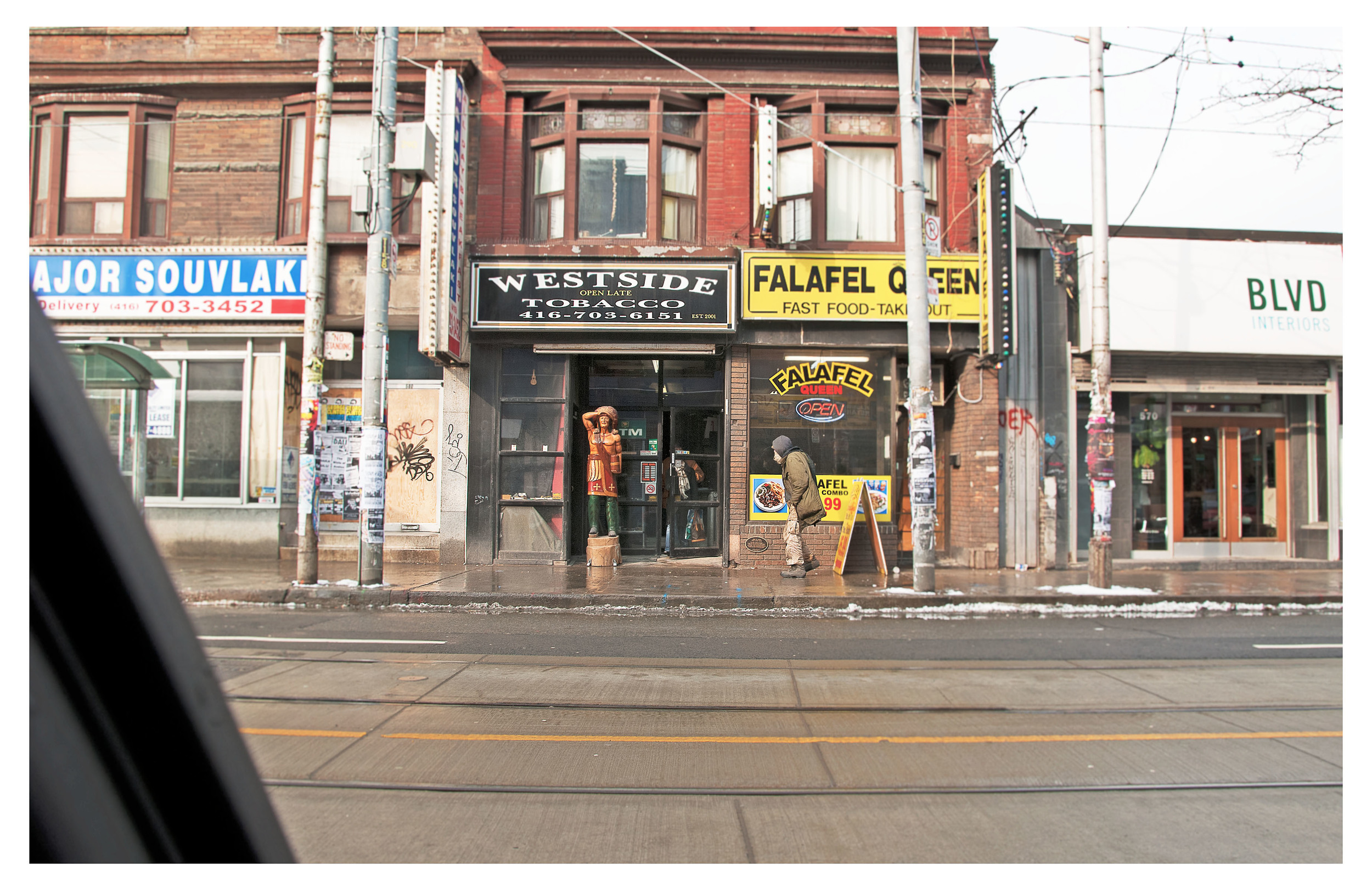

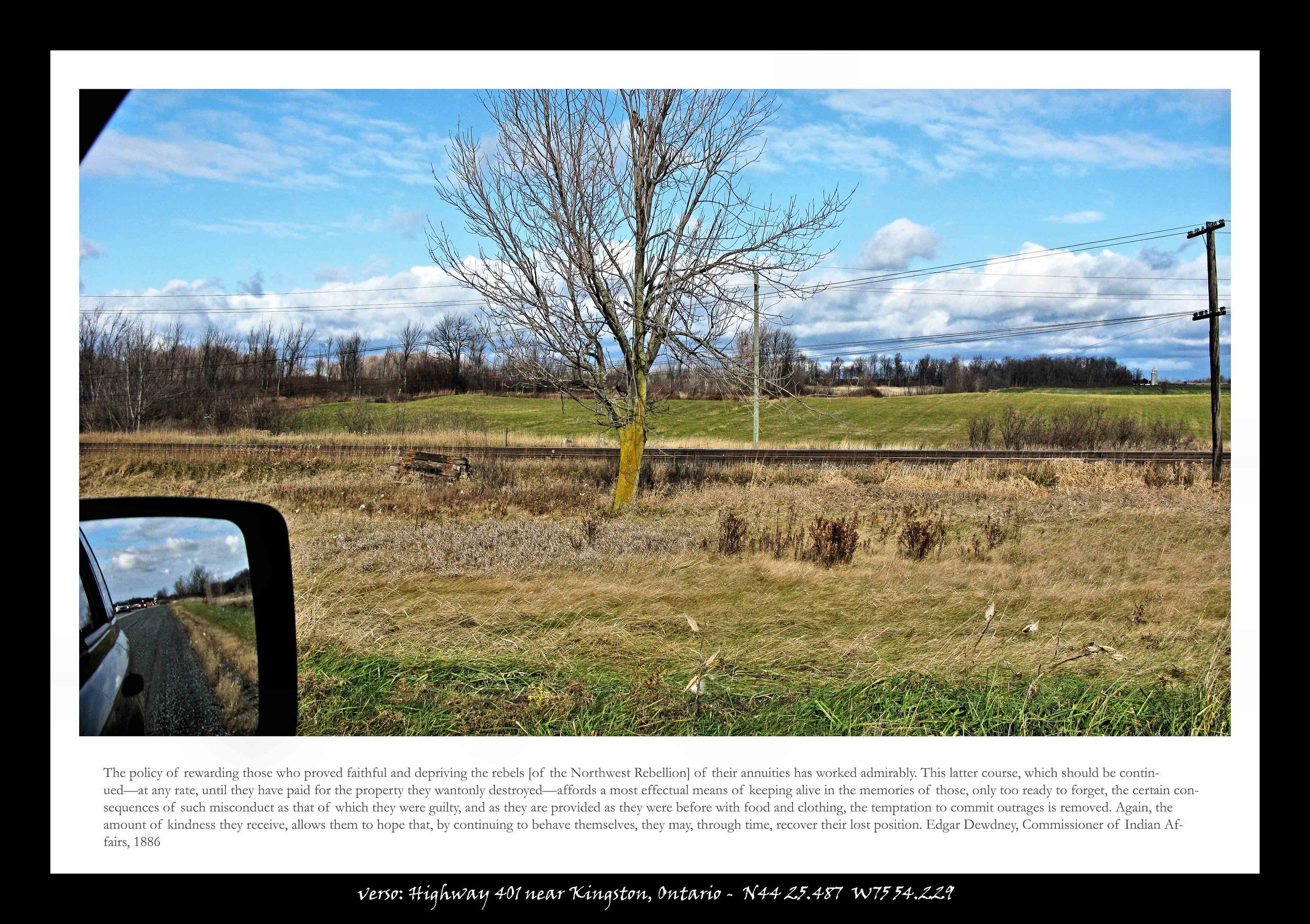

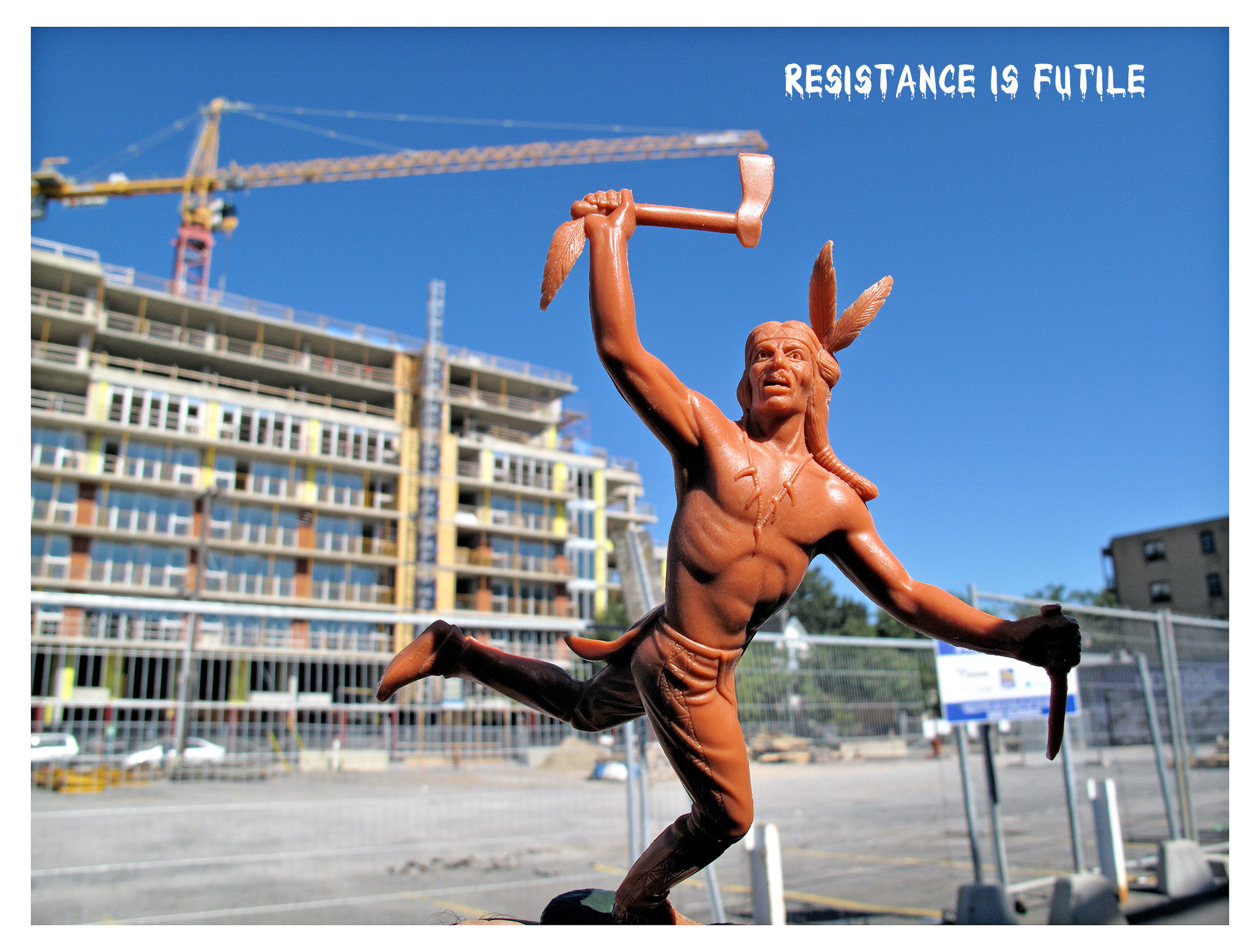

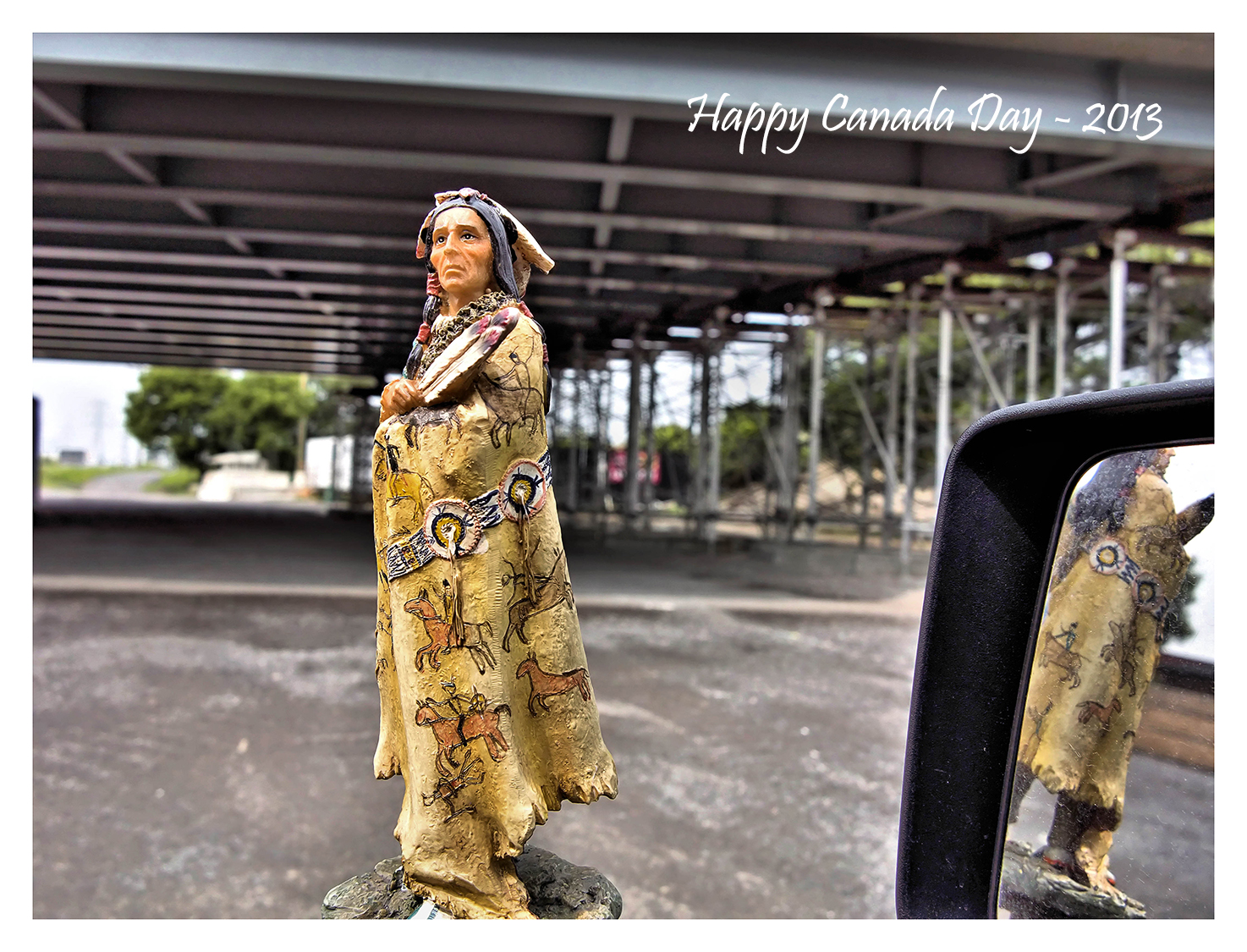

Jeff Thomas

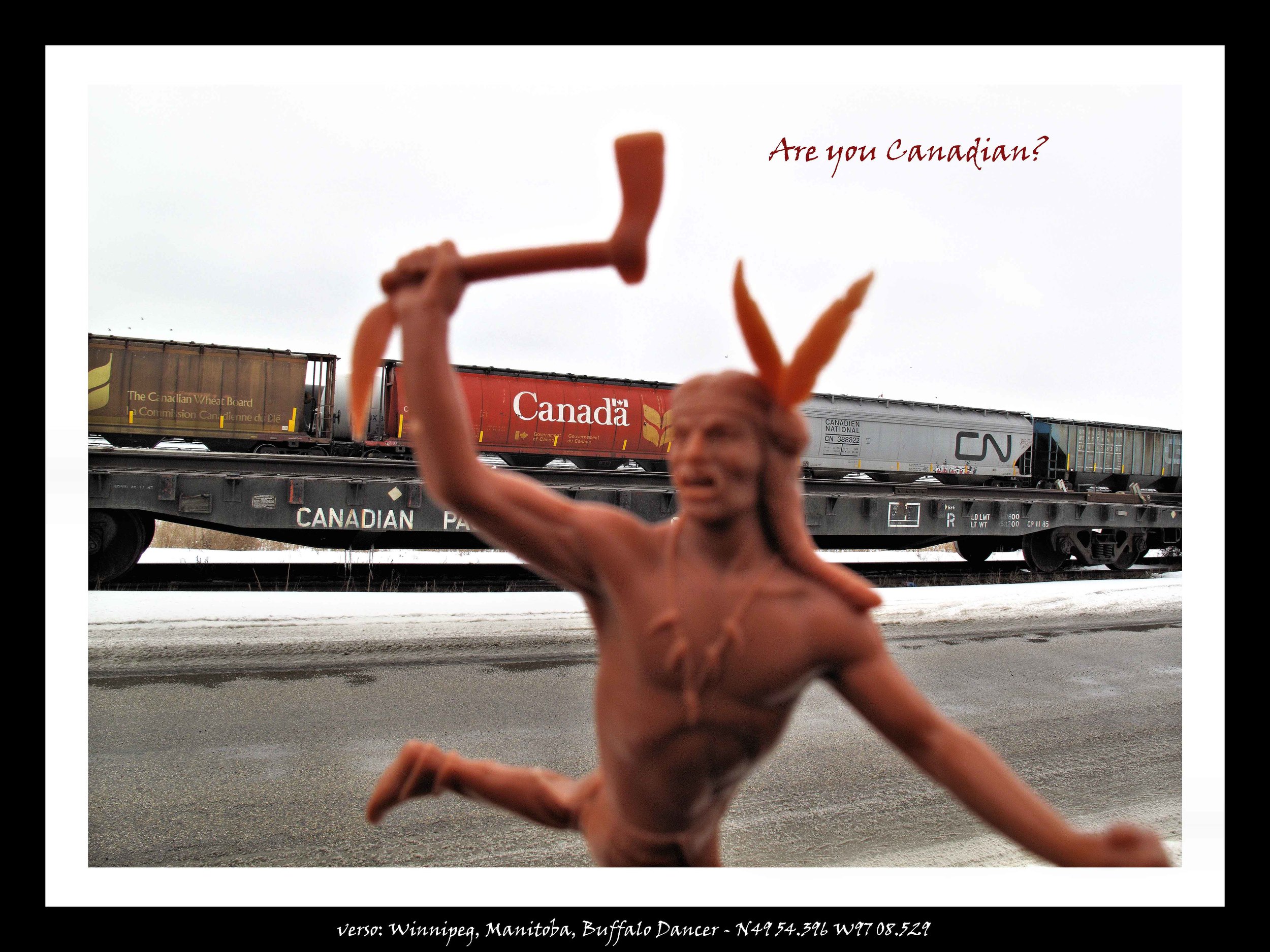

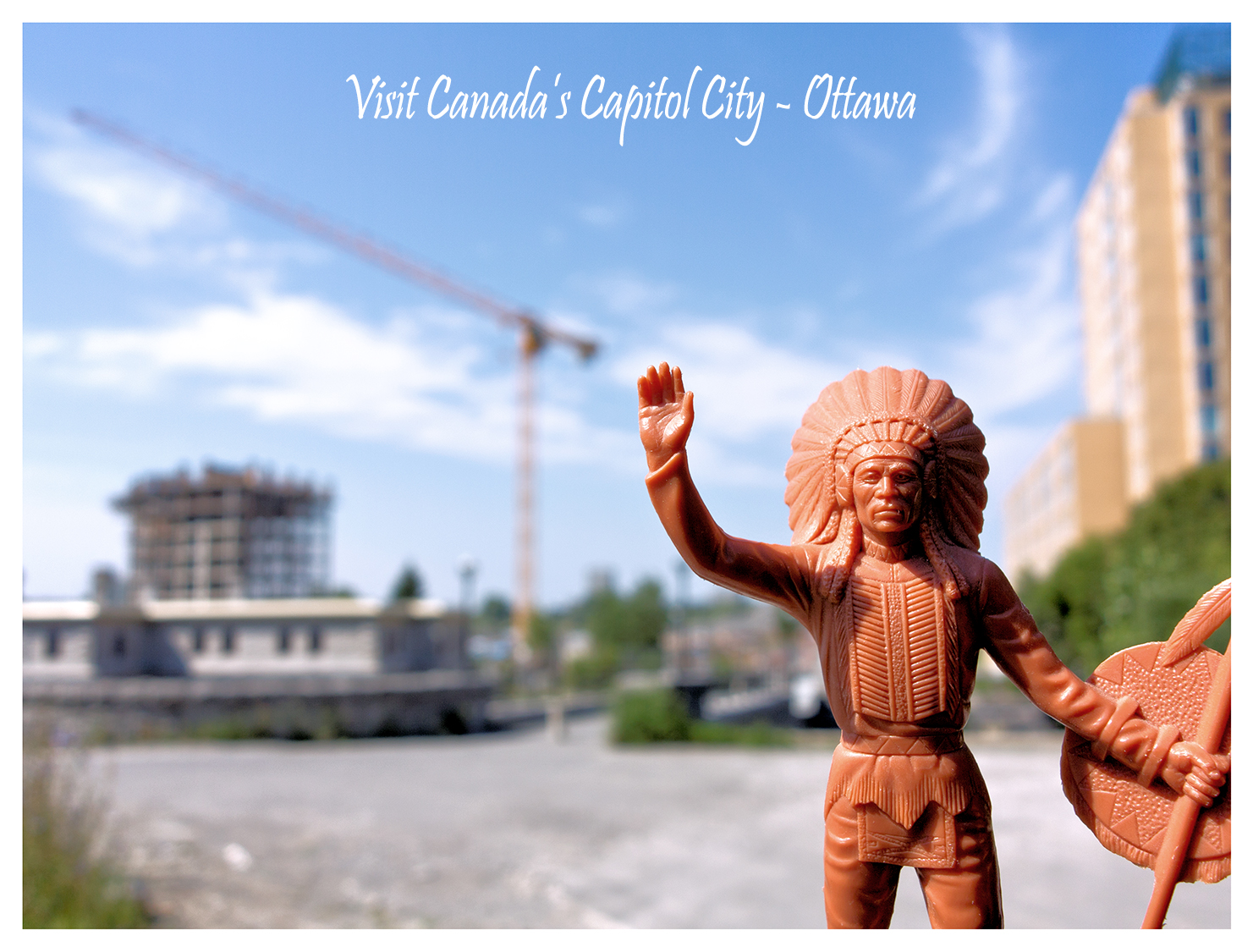

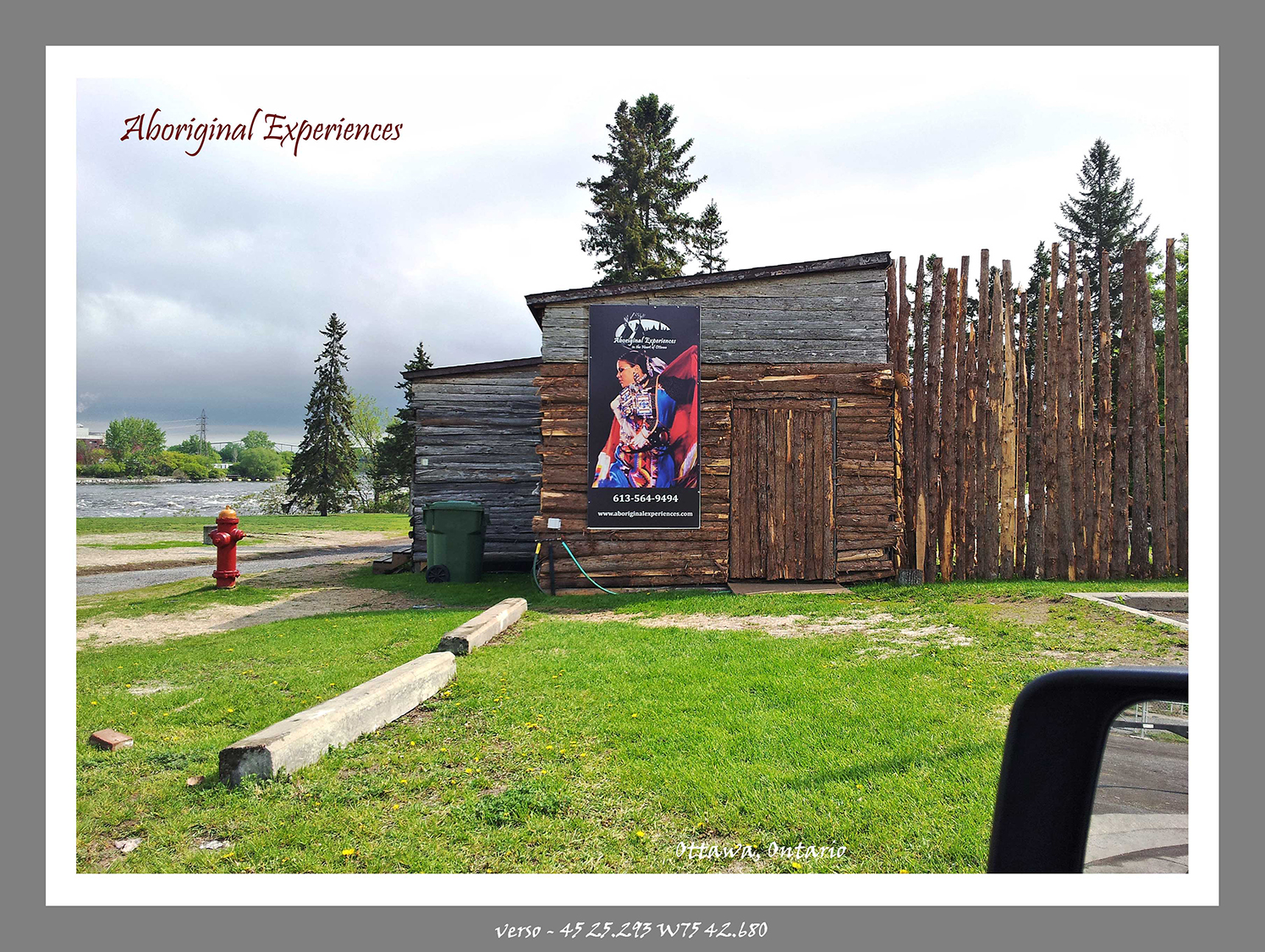

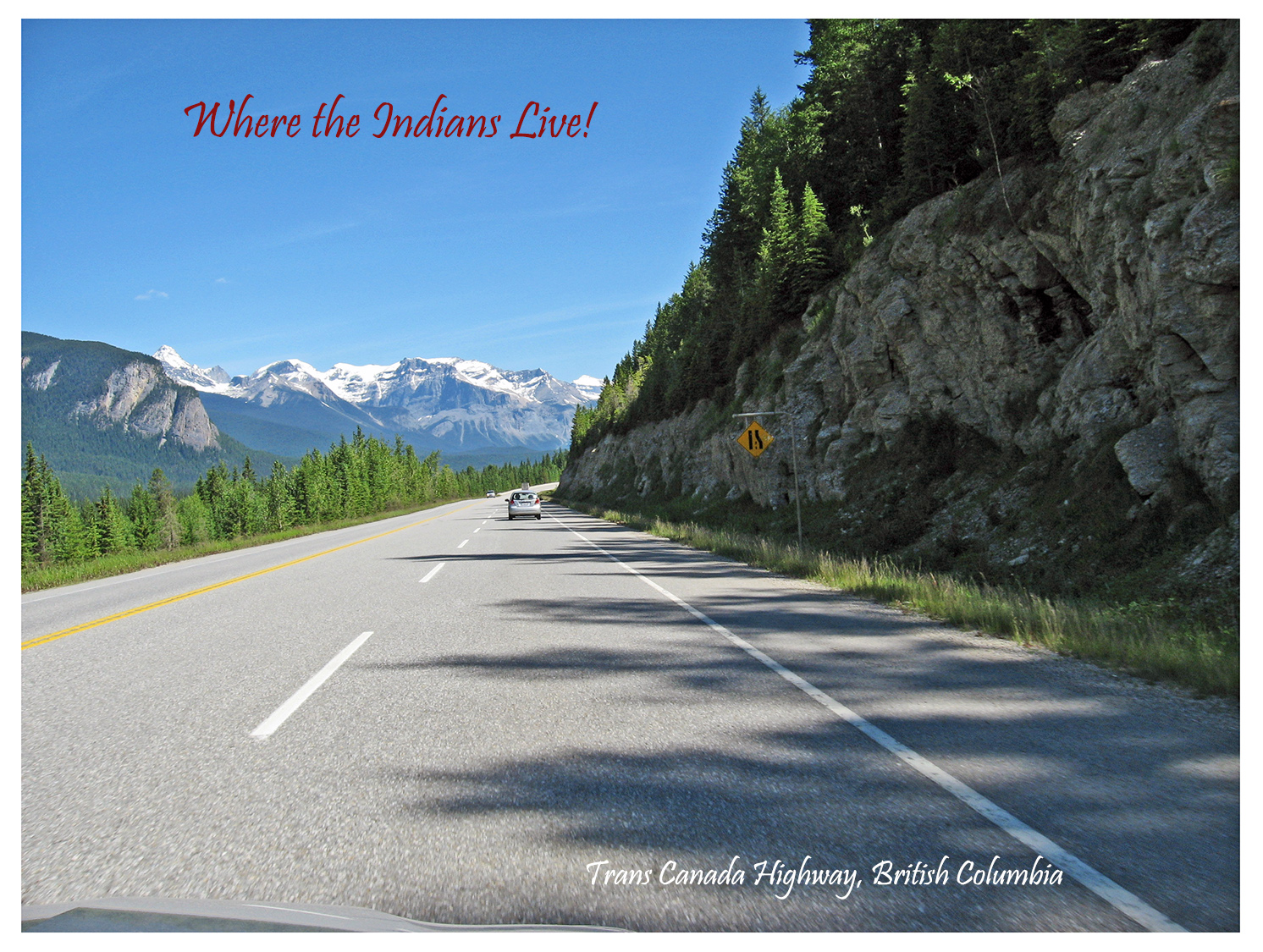

Jeff Thomas is an independent curator and photographer who deals in examination of his own history and identity, with issues of aboriginality that have arisen at the intersections of Native and non-Native cultures in what is now Ontario and northern New York state. Nationally recognized for ground-breaking scholarship and innovative curatorial practice in this area, he has been involved in major projects at such prominent cultural institutions in Canada as the Canadian Museum of Civilization, the Woodlands Cultural Centre, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and Library and Archives Canada.

As his curatorial projects, publications and exhibitions amply demonstrate he is committed to work dealing with issues of race, aboriginality, and gender in both archival and contemporary photography dealing with Aboriginal peoples. He is author of Where are the Children? Healing the Legacy of the Residential Schools, a ground-breaking exhibition sponsored by the Aboriginal Healing Foundation to publicly recognize, through photographic history, the Aboriginal experience of the residential school system in Canada. His research into historical Aboriginal experience and its contemporary relevance has also resulted in the Canadian Museum of Civilization project, Emergence from the Shadow: First People’s Photographic Perspectives, a critically-acclaimed study historical photographs by early 20th century Canadian anthropologists of members of the Six Nations community at Brantford, a show that provided contemporary members of that community their first access to these images of their ancestors and of historical life on the reserve.

It is not surprising, as a result, that he was commissioned to research and design the first Aboriginal intervention into the Euro-Canadian art installation at the Art Gallery of Ontario, No Escapin’ This: Confronting Images of Aboriginal Leadership. Intended to mark the institution’s new commitment to the introduction of Native history into the gallery’s spaces, No Escapin’ This has also effectively solidified Thomas’s place at the forefront of scholarship at the intersection of Native and non-Native histories in Canada.

Vanessa Dion Fletcher

Vanessa Dion Fletcher uses porcupine quills, Wampum belts and menstrual blood to reveal the complexities of what defines a body physically and culturally. She links these ideas to personal experiences with language, fluency and understanding. All of these themes are brought together in the context of her Potawatomi and Lenape ancestry, and her learning disability caused by a lack of short-term memory. These experiences have caused a fractured and politicized perspective of language.

In Writing Landscape 2010, Dion-Fletcher developed a technique of marking copper plates by wearing them on her feet and walking. “This work began in my mouth with my voice and moved down to my feet, and the earth.” In this project she uses this process to explore the significance of body, memory and geography. The finished work consists of the copper plates, intaglio prints made using the plates and video documentarian of the artist walking. This project is a way of recording and archiving outside of the inescapable colonialism associated with only being able to speak English.

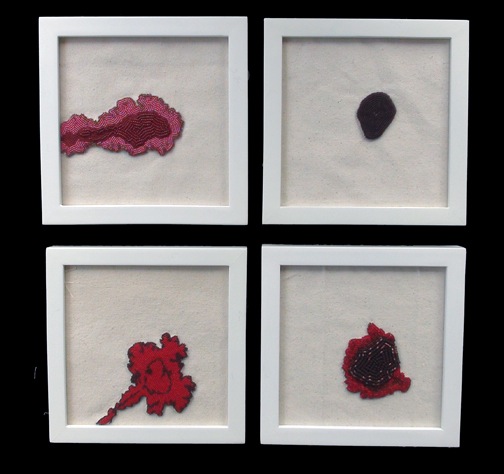

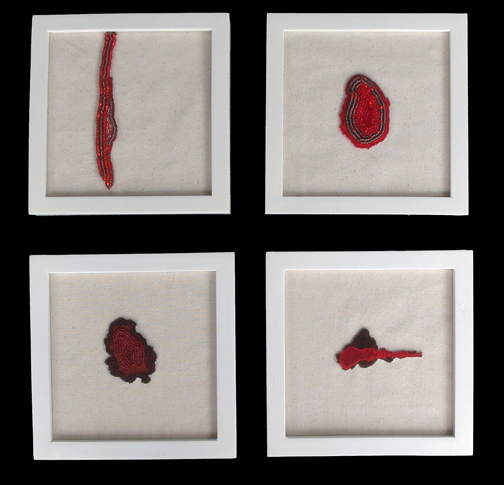

In Marked 2010-2013, Dion Fletcher produced a series of 13 beaded “stains” by recreating images of menstruation using glass beads. The process of learning how to bead and producing positive images of menstruation throw and indigenous artistic form reifies a positive image of the female indigenous body. Ultimately her work seeks to promote self-reflection and debate, and open communication among diverse populations.